Celebs

Ghana Dancehall Leader Shatta Wale

Dancehall is on the rise in Ghana and no one is waving its flag as proudly as Shatta Wale. A lot of artists these days refer to what they do as a movement. When Shatta Wale does it, it’s more than a rhetorical flourish. Born Charles Nii Armah Mensah Jr. in the suburbs of Accra, Ghana, the 31 year-old dancehall vocalist and producer rose to stardom over the last couple of years by delivering dancehall sermons and party jams to the nation’s youth. Now, leveraging the internet and his hard-won fanbase, Shatta is using his success to open a lane for dancehall in a country where the music industry is dominated by hiplife, a genre of hip-hop with elements of highlife and lyrics in Ghanaian languages like Twi. His efforts might just make him into the voice of a new generation in Ghana.

Dancehall is on the rise in Ghana and no one is waving its flag as proudly as Shatta Wale. A lot of artists these days refer to what they do as a movement. When Shatta Wale does it, it’s more than a rhetorical flourish. Born Charles Nii Armah Mensah Jr. in the suburbs of Accra, Ghana, the 31 year-old dancehall vocalist and producer rose to stardom over the last couple of years by delivering dancehall sermons and party jams to the nation’s youth. Now, leveraging the internet and his hard-won fanbase, Shatta is using his success to open a lane for dancehall in a country where the music industry is dominated by hiplife, a genre of hip-hop with elements of highlife and lyrics in Ghanaian languages like Twi. His efforts might just make him into the voice of a new generation in Ghana.

In an interview at the Ghanaian consulate in New York City during his recent North American tour, the kingpin dials his gravelly voice down to a deliberate rumble. “The dancehall scene is really growing very big now. It’s something that I fought for, for ten years. If you ask anyone in Ghana they’ll tell you I was the only person who stood for dancehall when the industry was trying to paint it black,” Wale asserts. Dancehall has a long history in Ghana, but it’s stayed underground, overshadowed by hip-hop and hiplife, and even the more established reggae culture.

Wale, whose father is a politician, comes from a family that loved the choir at church and reggae at home. He became immersed in dancehall as a young man when cousins from London started visiting and bringing new releases from Jamaica with them. In imitating favorite artists like Beenie Man, he found his own distinctive voice.

In 2004, his hit “Moko Hoo” brought him some attention under his former stage name, Bandana. A few other hits were followed by a nearly ten year hiatus without a concert, during which he supported himself as a producer. He cites a lack of radio support for his trouble. “DJs in Ghana, they didn’t want to play my music because they felt dancehall wasn’t our culture,” he says. Even now, as artists like Shatta Wale, Samini and Stonebwoy are increasingly breaking into the mainstream, few clubs book dancehall artists and few radio stations play their music. In contrast to hiplife, which you’ll hear on every radio, the dancehall scene revolves around massive all-day beach concerts that attract thousands of attendees — and word of mouth.

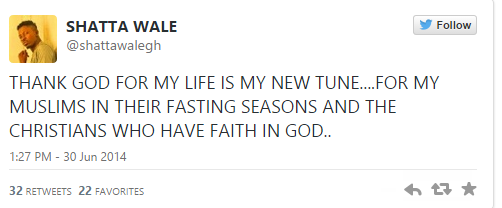

In the end, the singer didn’t need the airplay. Since the early 2000s, the internet has leveled the field for dancehall artists, allowing them to promote events and to release music without mainstream support. And no one has capitalized on this with as much verve as Shatta Wale. “If they are trying to stop us, I can let the world hear our music through that means,” he says with characteristic pugnacity. One of his many epithets is “president of social media.” “I’m always on there because that is what is helping me to build up,” he says.

In the end, the singer didn’t need the airplay. Since the early 2000s, the internet has leveled the field for dancehall artists, allowing them to promote events and to release music without mainstream support. And no one has capitalized on this with as much verve as Shatta Wale. “If they are trying to stop us, I can let the world hear our music through that means,” he says with characteristic pugnacity. One of his many epithets is “president of social media.” “I’m always on there because that is what is helping me to build up,” he says.

His success story is a long one but he’s willing to shorten it significantly for our interview: “One day I woke up and people were ordering my music. Everyone wanted to listen to Shatta’s music.” Since his big comeback in 2012, he’s worked tirelessly to stay on the public’s radar, releasing a steady stream of free MP3s. He does take on the odd brand ambassadorship, like many hiplife artists, but he largely prefers to make money in typically hardworking fashion: by playing lots of concerts.

To date, he has won several major industry awards in addition to Artist of the Year at the 2014 Vodafone Ghana Music Awards. These days you’ll hear his voice on the radio and in the clubs, not to mention see his face popping up on TV. He’s mashed it up from South Africa to the UK and performed with Akon, Mavado, and Popcaan. He’s going to Jamaica soon to shoot the video for “Party All Night,” his collaboration with Jamaican dancehall artist Jah Vinci. All of this is no thanks, by the way, to the tabloid press who he has told off on “Letter to the Media,” on which he barks “positive things I do dem attack” but declares “no bad mind can make me stop.”

He also famously caused a stir when he walked out of 2013′s Ghana Music Awards. He had been nominated for artist of the year but was passed over. It’s widely believed that he was robbed. He got up to leave in indignation, his supporters created a scene and he was escorted out. That night he composed and released the profanity-peppered song “Letter to Charter House,” on which he declares “me no need your award.” (Charterhouse produces the prestigious awards show.) This year, though he was awarded the coveted artist of the year title, he refused to attend the ceremony.

His energetic live shows might move Accra’s beach parties, but it’s this kind of outspokenness, coupled with his status as both an underdog and self-made man, that’s won him his loyal following and bulletproof street cred — even if it hasn’t endeared him to the media or the music industry. “I was always doing what the streets wanted. God being so good, from 2010 was the time I started going onstage, playing free shows, trying to exhibit what dancehall can mean for the yutes in Ghana. And up ’til now, people are giving me the kudos because they see that I fought the good fight and also the youth are learning from my music,” he observes. He knows that he owes his success to his young fans, especially those in Accra’s ghettoes. The same streets that once lifted up today’s hiplife and hip-hop stars like V.I.P. have now put the crown on his head.

His determination, integrity and open disdain for the establishment in what can be a socially conservative country has made him a hero to young people, who proudly claim “sm4lyf” (Shatta movement for life) in comments sections and on social media. Rab Bakari, a Ghanaian-American music executive and founding father of hiplife, explains what this means for Ghanaian music in a phone interview: “Every junior secondary school student probably wants to be like Shatta Wale now. You’re going to see ten more artists like Shatta Wale. It might even overshadow hiplife, gospel and reggae. Bakari has long been personally acquainted with the DIY deejay and confirms that the artist is already inspiring young Ghanaians to start making music without asking for permission. So, dancehall is coming.

Now that Shatta Wale has started to see a return on his long investment, he’s putting it back in, focusing on mentoring new artists and promoting unity in the dancehall scene. In particular, he supports those communities that have supported him as an artist, particularly his hardcore fans in the zongos, or marginalized, predominantly Muslim neighborhoods, such as Nima and Maamobi in Accra. The notorious Nima, where he keeps and apartment and his recording studio, is a second home to him. Even in the US he is managed by a group called Boogie Down Nima. He avers, “I cherish those places so much. I respect them so much. Even though I am a Christian, the Muslims have taken me to be an artist that they love so much. When you go to those communities you are going to find artists who are making waves all over. And those are place where I’ve tried to put up dancehall.”

In a tweet he dedicated his recent song “Thank God for My Life” to “My Muslims in their fasting season and the Christians who have faith in god.”

Muslims in Ghana are often discriminated against, so his embrace of the Muslim community is significant. Their returning his embrace, has in turn had a powerful effect on his career. Nima might be impoverished, but it is also the heart of Ghana’s underground music culture.

Always, conscious of his influence, Shatta Wale pushes a message of independence and perseverance: “The reason why I talk about yutes mostly is that I’ve been through the hustle and I really want them to see that if you are serious in whatever you are doing you can really get to wherever you want to get to.”

As if to further illustrate his point, Wale has recently taken up gold mining. (For real.) “I would encourage any youth to go and get a good license and get into it,” says the Dancehall star. And why not get into gold mining? For Shatta Wale, at least, it wouldn’t be the first time he’s followed a challenging and unlikely path to success.

Source: Beverly Bryan / MTV Iggy